Eszter Steierhoffer

Cosmic Dust: an interview with Sonia Leimer

2024

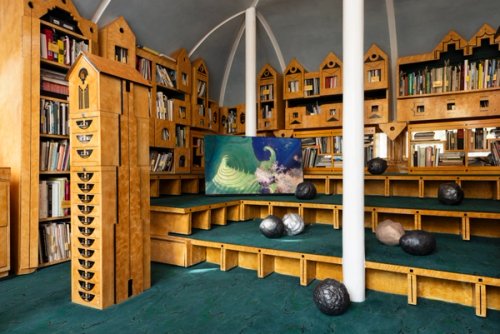

Sonia Leimer’s new exhibition Cosmic Dust is the first in the Jencks Foundation’s new thematic series on ‘Post-Modern Cosmology’: a theme which Charles Jencks developed both in his designs and through a series of seminars co-hosted with Maggie Keswick Jencks in Portrack, Scotland, to explore meaning in the cosmos in the intersection of science, religion and ecology. Leimer’s new exhibition explores the migratory system of cosmic dust through microscope photography, using them as inspiration for her ‘Dust Buddies’ sculptures made of bronze, aluminium and glass. The sculptures, which Leimer places in the Architecture Library of The Cosmic House, bring into view something that is typically invisible, and which connects the human and cosmic scales. In this interview with Jencks Foundation director Eszter Steierhoffer, Sonia Leimer talks about her research involving collaboration with the scientists of the Natural History Museum in Vienna, and why cosmic dust became so significant in her practice as an artist.

Eszter Steierhoffer (ES): It seems paradoxical to study the universe through a microscope. In your work you zoom in in order to zoom out, and think about the opposing scales of the cosmic and domestic as an interchangeable pair. What is cosmic dust and why is it so significant to you?

Sonia Leimer (SL): Cosmic dust is the oldest material that we can find on Earth. Around two-hundred or three-hundred tonnes of it fall to the surface of our planet every day, and some dust particles are as old as our solar system. In 2019, an international team of researchers reported that they found tiny grains of dust in a meteorite, fallen in Australia in 1969, that are even older than the solar system, and may be seven billion years old. What fascinates me as an artist is how these dust particles are shaped by nature when they enter our atmosphere. The heat melts their components, and they slow down, melting as they fall, which creates beautiful natural sculptures. I think in fact one dust particle lands on every square metre on Earth, which I find poetic – you can basically find these ancient materials all around us, everywhere.

ES: You were trained as an architect, and your work over the past decades mainly evolved in and around public space and the urban environment. How did you become interested in outer space, and what was your first encounter cosmic dust?

SL: My interest in dust began in 2018 when I made a silicone cast of part of Louise Bourgeois’ house on 20th Street, in New York – a narrow, nineteenth-century brick terraced house.

When I removed the silicone from the facade, it had picked up a thick layer of dust and dirt, which became my first encounter with the concept of urban dust. In my practice, I often work with garbage or leftover materials, so I eventually started focusing on space junk – remnants from our digital world. Then, I came across an article in the New York Times that mentioned two types of waste in space: man-made space junk and natural space dust, which is everywhere. That idea intrigued me, so I started to delve deeper into the topic of space dust.

ES: I was intrigued when you first came to The Cosmic House and proposed to collect dust as a way to create a portrait of the house and the city it is situated in. As part of this process, you also found some cosmic dust, or micrometeorites, which connect the urban dimension to vast cosmic proportions. Your close collaboration with the Natural History Museum allowed access to specialist equipment and opened up an extensive exchange with the scientists in Vienna. How did this collaboration come about, and can you describe this research journey?

SL: It was really important for me to have access to a high quality microscope such as the one at the Natural History Museum in Vienna. When I started using it, I also began conversations about dust with the scientists there. They examine dust every day, particularly cosmic dust, so it was different from just doing this at my studio. There was a lot of exchange between us, it was interesting for them to focus on urban or industrial dust, which they don’t usually study. They normally work with organic or cosmic dust. So in a way, my work got them to explore a new area – even though there isn’t a department specifically dedicated to that at the museum. After I collected dust from the roof of The Cosmic House, the Natural History Museum, in Vienna, helped prepare it. This means the dust was cleaned and separated into different types, industrial dust and cosmic dust, which is quite tricky as there are always some remnants. What was new for me in this project was that I learned to use the microscope myself. I spent many hours examining a single handful of dust, probably about a hundred hours in total. Over time, I became familiar with each individual grain, it was like entering a city and getting to know the streets and the buildings. The more time I spent in this microscopic world, the more I was able to detect cosmic dust particles; you start to get an eye for them.

ES: What sets apart organic dust from industrial dust?

SL: The shape of cosmic dust is very special. Many of these dust grains are very deep, dark in colour, and they are non-reflective. They often have beautiful round, circular shapes on their surface, and some even have little glass dots at their core. After a while, you start to recognise them. Some grains resemble a turtle’s back, some are entirely made of glass. One thing that perhaps ties them all together is their droplet-like form, shaped by gravitational forces when they enter the atmosphere. As the lower part melts from the heat, it turns into glass, and the upper part remains slightly bigger.

ES: You once told me that to move these dust particles under the microscope, one needs to use a tool which is thinner than human hair. How did you arrive from these two-dimensional microscopic images to the sculptures – your ‘Dust Buddies’?

SL: When you look at them under the microscope, these dust particles are so beautiful, and I thought it would be wonderful to actually have them in physical space, to experience them all the time. I did not want to make exact copies of the original dust grains, but rather take inspiration from this microscopic world and translate it into sculptures. So I started photographing dust grains that I found particularly interesting in form, and from there I created sculptural versions of them. Some are closer to the original dust grains, while others are more freely inspired. They are made of different materials, such as glass, bronze and aluminium, and have a range of colours. And I think when displayed together, they highlight the uniqueness of each dust particle, which is so fascinating – each grain is truly unique.

ES: How did you end up with the title ‘Dust Buddies’?

SL: When I was looking through the microscope at the Natural History Museum, I started to get attached to certain dust grains – they began to feel like little creatures I encountered in this tiny world. I saw them as friends, like companions in this microscopic space, so I originally thought to call them ‘Dust Bodies’, because they seemed to have a physical presence. But then I liked the idea of them being more like dust buddies, almost like little dust friends you have around, even in my own home or in my studio.

ES: It's interesting how dust has a negative connotation in our everyday lives (it implies housework!), whereas in recent scientific research it has become an important new subject. Space dust, once perceived as an obstacle to observing the solar system, is now a key area of research as scientists have realised it can convey vital information about the origins of our universe.

SL: I feel that dust, especially in the last five years, has become linked to discussions around ecology and climate change. Dust is always in movement – it migrates from one continent to another, it doesn’t stay in the same place. That’s also something that interested me about it. Space dust is also gaining more attention. I think it partly has to do with advancements in technology. New microscopes allow us to see the microscopic world in much more detail. This evolving imaging equipment has made it possible to detect and study dust in ways we couldn’t before. But also in recent years there are issues with dust becoming more visible, and often more dangerous, for example in cities. Additionally, there are more public projects involving dust. In Europe, for example, some natural history museums are inviting citizens to look for cosmic dust, which I find fascinating because it's a form of science that is shared with the public. In the context of The Cosmic House, also considering Charles Jencks’ interest in scaling and cosmology, it felt fitting to search for cosmic dust right on its roof.

ES: You visited The Cosmic House several times over the past two years and engaged with Charles’ archive in depth. First you studied the history and design of The Cosmic House itself, and then other aspects of Charles' work and land art project in Portrack that implies a different and perhaps more direct involvement with science and cosmology. Could you talk about this encounter and how it led to the new body of work that you are showing at the house?

SL: I think the ‘Dust Buddies’ fit the house really well, because they come from such a distant place and Charles was interested in looking at the biggest possible picture – the galaxy, and the world’s place within it – and bringing it into the house. That’s where our ideas overlap: we both try to take the broadest perspective possible and bring it as close-up as possible. The Cosmic House is filled with references to the cosmos, like the Sun Table or the Sun Chair. The theme of cosmology is woven into the entire design: in colours and textures, and down to how the house interacts with sunlight. I think it’s about perceiving Earth as a connected part of the cosmos and thinking of our planet as part of that bigger picture. But anyway, I think that idea resonates with both his work and mine, and that connection between nature and the cosmos is central to this new body of work.

ES: Your film relies on imagery and audio-visual recordings from various different locations, not only from the house, but also from the Garden of Cosmic Speculation outside it, which you filmed from a bird’s eye view using a drone. This is juxtaposed with close-up interior images of The Cosmic House, an unusual way of portraying architectural space, almost as if looking through a microscope. You have also recorded images through an actual microscope, in Vienna. Why did you become interested in microscopic imagery and how has this informed your artistic process?

SL: For me, it was wonderful to look at dust through that microscope, with that level of sharpness and resolution. That's why I wanted to film my microscope sessions and share the experience. Navigating through that micro-world was so captivating, I could spend hours looking at the high-resolution images with all those colours. The methodology of filtering and studying the dust is very much based on its visual appearance, and I think that’s what makes it so interesting to film. What’s also remarkable is that the cosmic dust grains that we detected were later analysed scientifically. There’s this overlap between the scientific and artistic work – my process of finding and presenting the dust intersects with the museum’s detailed analysis, which happens at a later moment. I like that the scientific work takes the project beyond my own involvement, allowing me to share part of the process.

ES: You also seem to have an ever-growing micrometeorite collection.

SL: Yes, I have three right next to me on the desk! It's my small collection, and I plan to bring them to London …